New studies show that trauma biologically alters the brains of young boys in ways that affect their adult behavior.

June 22, 2015, 1:35 PM, CDT

A version of this story ran in the June 2015 issue.

This is the fourth, and final, story in a series.

Juan Ramirez grew up in poverty in the Rio Grande Valley, in a neighborhood infested with drug-and gang-related violence. By the age of 10 he’d started smoking marijuana and using inhalants. Within a couple of years he’d moved on to cocaine. By his middle teens he was drinking alcohol and smoking weed daily. A game he and his friends used to play in the Valley, called WAWA, involved spraying paint into a bag, sealing the lip around their mouths, and inhaling the fumes to get high.

Ramirez is the middle of five children and, according to court documents, his mother and father were alcoholics who disciplined their kids by whipping them with belts, clothes hangers, shoes—even tree branches. The severity of those beatings depended on the parents’ moods. Consequently, Ramirez spent most of his time playing outside in the street.

Inevitably, perhaps, he dropped out of school, became a drug addict and spent time in Texas Youth Commission facilities for juvenile offenders. But it was a single incident in 2003 that sealed his fate. One night in early January, 11 masked men burst into a small house in Hidalgo County to steal marijuana. By the time they left, six members of a rival drug gang in the house were dead. Ramirez was just 20 years old and the youngest of those the police said were responsible. Although he wasn’t identified as the gunman, under Texas’ law of parties, prosecutors successfully sought the death penalty.

For the uninitiated, the law of parties holds that if a person “solicits, encourages, directs, aids, or attempts to aid the other person to commit the offense,” then he or she is criminally responsible for the conduct of the other person. Of course the law can be applied inconsistently—and it often is.

This is Ramirez’s 11th year on death row, housed at the notorious Polunsky Unit in the rural East Texas town of Livingston. And his is one of numerous stories of childhood abuse and violence that condemned inmates have told the Observer as part of an informal yet wide-ranging survey of the men waiting for Texas to exercise the most brutal manifestation of its power.

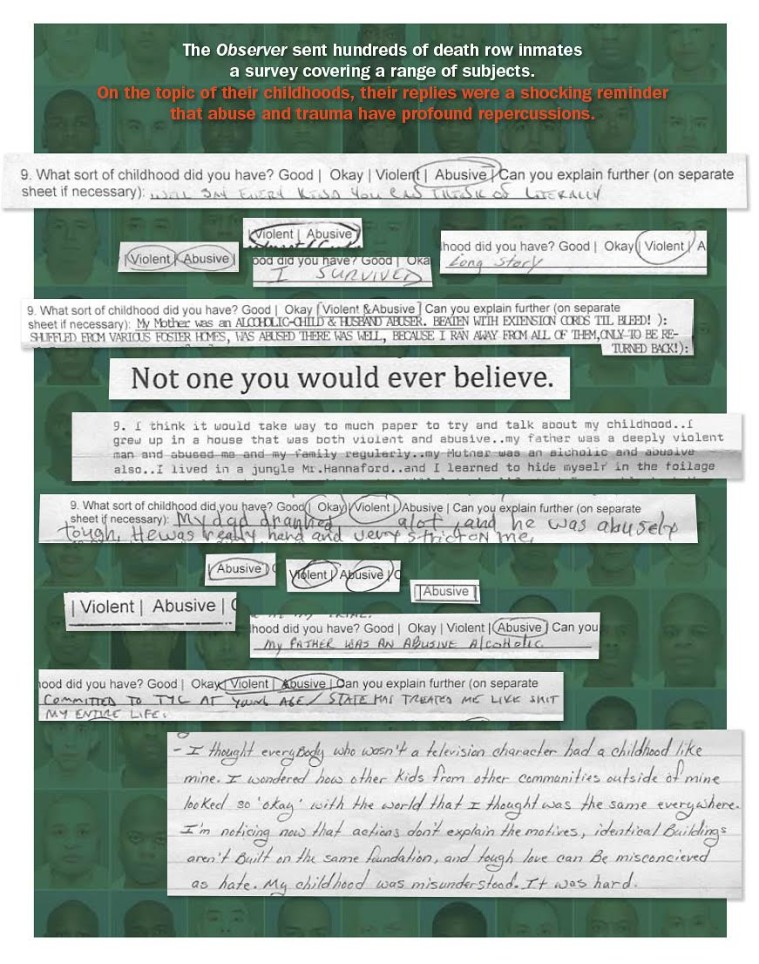

Last year, I sent a questionnaire to each of the 292 inmates on Texas’ death row. It was designed to elicit information often missed in narratives about the death penalty: the effect that solitary confinement has on them; whether they had found religion in prison; and what sort of childhoods they had. I wanted to see if any patterns emerged.

Forty-one inmates responded. Ramirez was among 22 inmates (54 percent) who reported having violent or abusive childhoods. An additional nine inmates (22 percent) described their childhoods as “hard,” or said they had some sort of dominant negative issue—whether it was growing up in poverty and/or in a crime-filled neighborhood or that they endured the potentially debilitating experience of having a parent walk out on them. This is the final story in a series based on information obtained from those responses. Three others, which explore what books the inmates read, the effects of solitary confinement, and how religion factors into their lives, ran previously on the Observer website.

This is not an attempt to retry those cases or to mitigate the harm these men caused. But too often, defense attorneys lack the resources to launch in-depth investigations into the backgrounds of those facing capital convictions. And to quote the Death Penalty Information Center, “Almost all defendants in capital cases cannot afford their own attorneys. In many cases, the appointed attorneys are overworked, underpaid, or lacking the trial experience required for death penalty cases.” The center cites a Dallas Morning News examination of 461 capital cases that found nearly one in four inmates was represented at trial or on appeal by court-appointed attorneys who had been disciplined for professional misconduct. Additionally, an investigation by the Texas Defender Service found death row inmates “faced a one-in-three chance of being executed without having the case properly investigated by a competent attorney.”

It’s also important to acknowledge that the stories of inmates’ childhoods that have emerged from the Observer’s survey are told in the inmates’ own words. When possible, they have been corroborated with court documents or contextualized by news reports.

The responses in our correspondence offer new evidence that supports findings from studies that show a correlation between childhood trauma and the potential for future violent offending. As Texas leads the nation’s death penalty states in executions, the letters also act as important reminders that it’s time we ask what this says about the fractured minds of those we execute and rethink the extent of our moral culpability.

At his trial, prosecutors said Ramirez was a member of a Rio Grande Valley gang known as the Tri-City Bombers. But of the 11 alleged perpetrators of what became known as the Edinburg Massacre, only two received a death sentence. Another, Robert Garza, was executed in 2013 for an unrelated offense. That same year, the alleged ringleader of the gang, Jeffrey Juarez, known as “Dragon,” got 20 years for drug conspiracy and trafficking but escaped prosecution for the killings in Edinburg due to lack of witnesses. Likewise, Reymundo Sauceda, who prosecutors said approved the homicides, had the capital murder indictment against him dismissed. The others in the gang either received prison terms or remain fugitives from the law.

In a letter to the Observer, Ramirez wrote, “I come from the poorest region of the nation, from a poor household. I pretty much had all the strikes against me before I had a choice of my own.”

In their paper “The Cycle of Violence,” published by the American Psychological Association, David Lisak and Sara Beszterczey, researchers at the University of Massachusetts Boston, looked at the life histories of 43 men on death row. They discovered that all of them reported having been neglected as children, that an astonishing 94 percent had been physically abused, 59 percent sexually abused, and 83 percent had witnessed violence in adolescence.

Another study, “Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adult Criminality,” published in 2013 in The (Kaiser) Permanente Journal, surveyed 151 offenders and compared their answers with a “normative sample” of the population. The researchers found that the offender group reported nearly four times as many adverse events in childhood as the control group.

Ochberg said it’s not simply learned behavior. “There are a lot of people exposed to a great deal of violence and vengeance every day and they don’t behave in this violent, destructive, criminal way,” he said. “It’s also clear that not all criminality is the product of childhood abuse. But these early adverse situations reduce the resilience of human biology and they change us in very fundamental ways. Our brains are altered. And that’s what this research is bearing out.”

Most stories about the death penalty begin with the moment of violence—that one, often unplanned and unforeseen episode that changed everything.

These stories—in newspapers, magazines and in documentary film—discuss the minutiae of the crime, perhaps relay some element of repentance on behalf of the convicted inmate, and often include interviews with the victim’s family. But what most of these narratives lack is an attempt to establish what went before by taking us back even further into the life of the condemned, before he committed any crime, to that incubation period that molded him—to the trauma. And often that’s the key to unlocking the “why” in these stories.

Just last year, Jeffery Prevost, a 54-year-old auto mechanic, was condemned to die by lethal injection for brutally torturing and killing his former girlfriend and her son after she had broken up with him. Prevost’s defense attorney, Allen Tanner, told the court that his client had had traumatic relationships with women that could be traced back to the time his sister choked to death—an incident that caused his mother to spend the remainder of her life in and out of mental hospitals. What’s more, Tanner said, his client had a daughter who was born with a birth defect and died before the age of 2. But it didn’t sway the jury.

One of the more high-profile cases where childhood trauma has been raised (too late, unfortunately) in mitigating the crime is that of Johnny Frank Garrett, executed in 1992 for the brutal rape and murder of a nun 11 years earlier—a crime he committed when he was 17. As Amnesty International notes, the execution went ahead despite Garrett’s history of childhood abuse and severe mental illness.

According to Amnesty, Garrett was raped by his stepfather, introduced to alcohol and various drugs by family members when he was 10, and forced to perform sexual acts in pornographic films from the age of 14 at the behest of his stepfather, who also hired him out to other men for sex. He was regularly beaten, and once placed on the burner of a stove, resulting in severe scarring, according to Amnesty. The organization says none of this information was made available to the jury at his trial. Though he received a 30-day reprieve from then-Gov. Ann Richards after Pope John Paul II appealed for clemency, Garrett was ultimately executed after Texas’ Board of Pardons and Paroles voted not to commute his sentence.

Ruben Gutierrez was convicted of murder in 1999 under Texas’ “Law of Parties.” He says he had nothing to do with the killing.